welcome to the worlld

We build buildings which are terribly restless. And buildings don’t go anywhere. They shouldn’t be restless.

Minoru Yamasaki

I write to you on February 3rd, two weeks before you’re due to arrive but I imagine it will be much longer before you ever read this. Between now and then you will learn the meanings of many words and concepts and hopefully begin to identify the places where there isn’t any meaning, and if you can, help me to do the same. I had been interested in infrastructure, how utilities like water and electricity typify systemic problems of access and distribution and how in our relationship to the endpoints of systems, it’s easy to forget the unseen mechanism providing a resource and at what costs. I began thinking about intermediary places and how they relate to our dwindling privacy in the internet age; how that concept is different than what private means in a corporate sense, and how many of the places we consider public - plazas, pedestrian malls, parks – are owned, as a real estate holding, as an object.

I wasn’t sure I bought it either; while these things are true, they are not revelations. I grew more interested in what people do at these precipices, how a site or object can be used for varied motives, and how that is both hopeful and frightening. The western notion of the public square originated in Ancient Greece where there was a forum called the agora, referring equally to the place and the gathering of people that met there. This is where the term agoraphobia comes from, a fear of public spaces and large crowds, which has taken on new meaning in an era of mass shooting events, natural disasters and political violence - sites of community turned sites of tragedy. These dualities are present everywhere, in our very language: to carry: a weapon, a disease, a child.

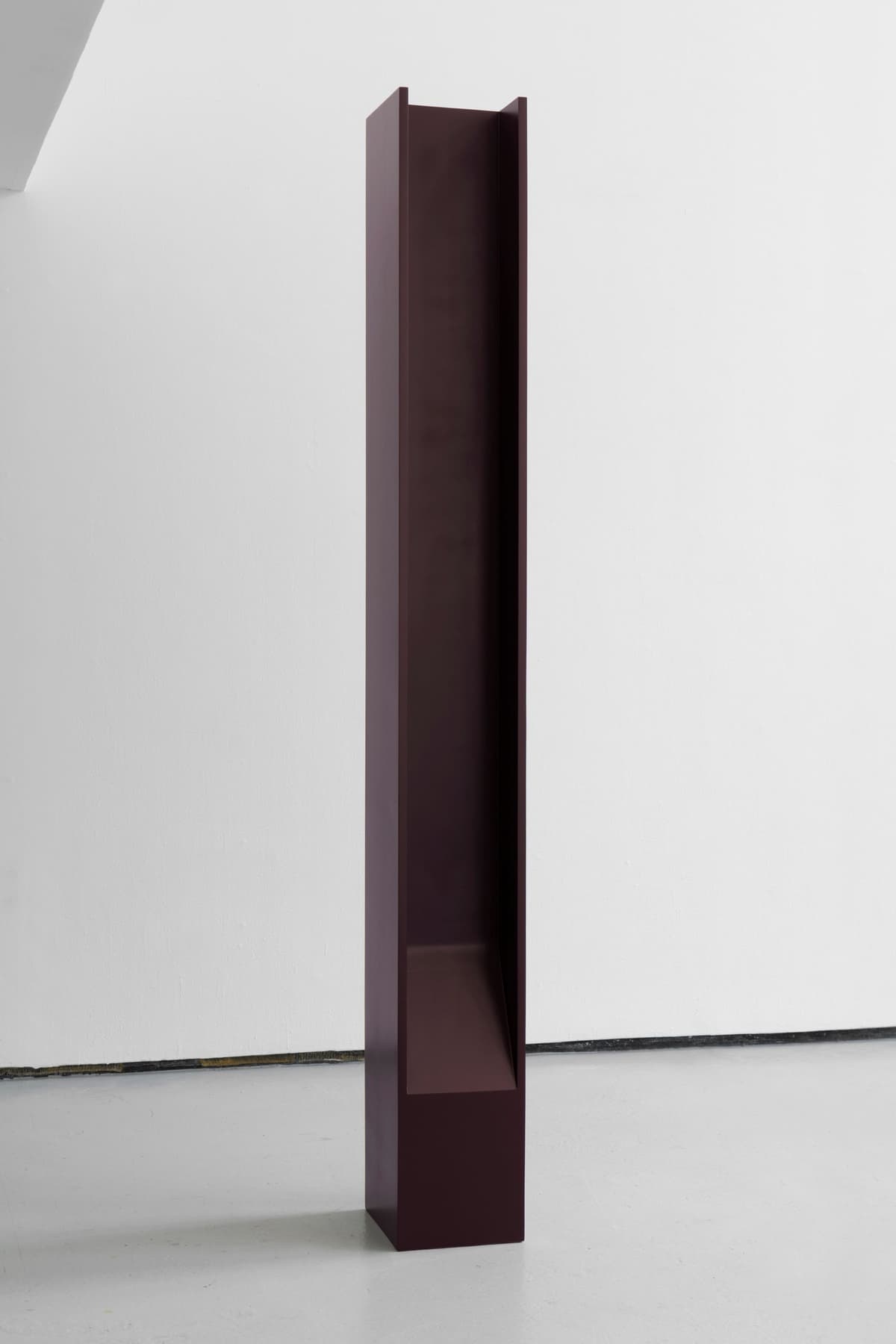

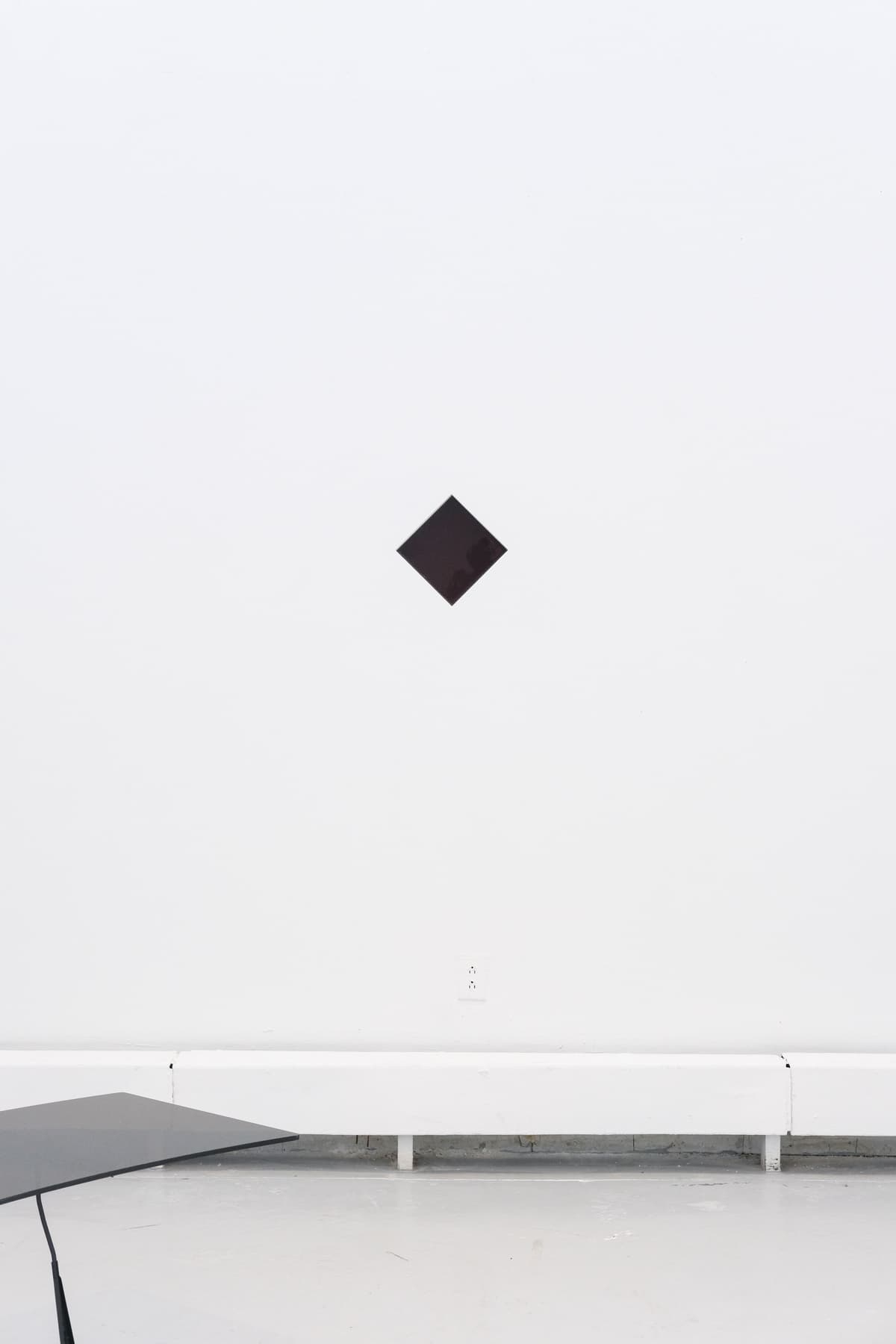

I planned to make a group of sculptures, reproductions of objects from these places and elaborating a series of relationships between their historical significance: a defunct thermometer from a 19th century newspaper once headquartered in Lower Manhattan; an iron water pump from the 1854 Cholera outbreak in South London; a nylon rendering of a box truck’s roll gate, like of those used to deliver vegetables to farmer’s markets or in numerous vehicular attacks on pedestrians. I decided that what these motifs have most in common is their existence as technologies; each are ways to subjugate our natural world and, in each instance, they have failed, or we have failed ourselves through using them. If this is the proven trajectory of production, why do we keep producing? Despite this observation, we spin the wheel, afraid to see what happens when it finally stops turning.

When a skyscraper is constructed, it includes a large device called a Tuned Mass Damper, an internal steel weight rigged to compensate for the oscillations of the building enacted by winds. It looks like a sun sliced into latitudinal pieces, cradled and held taut by spring cables connected to the structural framework; imagine the middle sphere of a pendulum, unmovable, despite repeated force from either direction. In many mythologies, the sun was said to be carried across the sky from east to west in a chariot driven by a god; like the sun, it is not the damper that moves, but the bodies that orbit it, collectively stabilizing themselves amidst a greater force. This predilection towards centers neglects the randomness of the universe as an entirety, and yet in the case of towers it must be defined, to accommodate gravity and the comfort of the people within them. We must ignore how odd it is to be so high above the ground. The closest some of us will ever get to heaven.

It is not yet light, but silhouettes of the plaza take shape as the sun slowly rises from the eastward streets, a chalky blue dawn, gradually warming. Below, the trains pass with increasing frequency, their hissing blends together as the rails heat up and grease. At the street corners, from porticos into the ground, people emerge, a few each minute, their steps decisive, faithful to a practiced way. The elevator banks will collect these people and carry them to different floors of the buildings, their office lights brightening, pin pricks against the coastal sky. There’s something excruciating about the fidelity, knowing that regardless of what happens to us, this orchestration will repeat, in some way, forever. Maybe I’ve always been here, waiting for you to arrive.